Richard Owen Review of Origin and Other Works Summary

| Richard Owen | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Owen, c. 1878 | |

| Built-in | (1804-07-twenty)20 July 1804 Lancaster, England |

| Died | xviii December 1892(1892-12-xviii) (anile 88) Richmond Park, London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh St Bartholomew'due south Hospital |

| Known for | Coining the term dinosaur, presenting them as a distinct taxonomic grouping. British Museum of Natural History |

| Awards | Wollaston Medal (1838) Royal Medal (1846) Copley Medal (1851) Baly Medal (1869) Clarke Medal (1878) Linnean Medal (1888) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Comparative anatomy Paleontology Zoology[i] Biology[1] |

Sir Richard Owen KCB FRMS FRS (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English language biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Despite being a controversial figure, Owen is generally considered to take been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owen produced a vast assortment of scientific work, but is probably best remembered today for coining the discussion Dinosauria (meaning "Terrible Reptile" or "Fearfully Great Reptile").[2] [3] An outspoken critic of Charles Darwin'southward theory of evolution by natural choice, Owen agreed with Darwin that development occurred, but thought it was more complex than outlined in Darwin's On the Origin of Species.[4] Owen's approach to evolution can be considered to have predictable the issues that have gained greater attention with the contempo emergence of evolutionary developmental biological science.[5]

Owen was the first president of the Microscopical Society of London in 1839 and edited many issues of its periodical – and so known as The Microscopic Journal.[6]

Owen likewise campaigned for the natural specimens in the British Museum to exist given a new domicile. This resulted in the establishment, in 1881, of the now earth-famous Natural History Museum in Due south Kensington, London.[seven] Bill Bryson argues that, "past making the Natural History Museum an institution for anybody, Owen transformed our expectations of what museums are for".[eight]

While he made several contributions to science and public learning, Owen was a controversial figure among his contemporaries, such as Thomas Henry Huxley. His later career was tainted by controversies, many of which involved accusations that he took credit for other people'south work.

Biography

Owen was built-in in Lancaster in 1804, ane of half-dozen children of a West Indian Merchant named Richard Owen (1754–1809). His female parent, Catherine Longworth (née Parrin), was descended from Huguenots and he was educated at Lancaster Royal Grammar School. In 1820, he was apprenticed to a local surgeon and apothecary and, in 1824, he proceeded equally a medical student to the Academy of Edinburgh. He left the university in the following year and completed his medical course in St Bartholomew's Infirmary, London, where he came under the influence of the eminent surgeon John Abernethy.

In July 1835 Owen married Caroline Amelia Clift in St Pancras past whom he had one son, William Owen. He outlived both wife and son. After his death, in 1892, he was survived by his three grandchildren and girl-in-police Emily Owen, to whom he left much of his £33,000 fortune.

Upon completing his education, he accepted the position of assistant to William Clift, conservator of the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, on the suggestion of Abernethy. This occupation led him to abandon medical practise in favor of scientific enquiry. He prepared a serial of catalogues of the Hunterian Collection, in the Majestic College of Surgeons and, in the form of this work, he acquired a noesis of comparative beefcake that facilitated his researches on the remains of extinct animals.

In 1836, Owen was appointed Hunterian professor, in the Royal Higher of Surgeons and, in 1849, he succeeded Clift as conservator. He held the latter office until 1856, when he became superintendent of the natural history department of the British Museum. He then devoted much of his energies to a slap-up scheme for a National Museum of Natural History, which somewhen resulted in the removal of the natural history collections of the British Museum to a new building at Due south Kensington: the British Museum (Natural History) (at present the Natural History Museum). He retained function until the completion of this work, in December 1883, when he was fabricated a knight of the Order of the Bath.[ix] He lived quietly in retirement at Sheen Lodge, Richmond Park, until his death in 1892.

Sheen Club, Richmond Park, home of Owen

His career was tainted by accusations that he failed to give credit to the work of others and even tried to appropriate it in his own name. This came to a head in 1846, when he was awarded the Imperial Medal for a paper he had written on belemnites. Owen had failed to admit that the belemnite had been discovered past Chaning Pearce, an amateur biologist, four years before. As a result of the ensuing scandal, he was voted off the councils of the Zoological Lodge and the Imperial Society.

Owen always tended to support orthodox men of science and the status quo. The royal family unit presented him with the cottage in Richmond Park and Robert Peel put him on the Civil Listing. In 1843, he was elected a strange member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In 1844 he became an associated member of the Regal Found of kingdom of the netherlands. When this Institute became the Imperial Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1851, he joined as strange member.[ten] In 1845, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[xi]

He died at domicile on fifteen December 1892 and is buried in the churchyard at St Andrew's Church, Ham near Richmond, Surrey.[12]

Work on invertebrates

While occupied with the cataloguing of the Hunterian drove, Owen did non confine his attention to the preparations before him only besides seized every opportunity to dissect fresh subjects. He was immune to examine all animals that died in London Zoo's gardens and, when the Zoo began to publish scientific proceedings, in 1831, he was the most prolific correspondent of anatomical papers. His first notable publication, withal, was his Memoir on the Pearly Nautilus (London, 1832), which was soon recognized as a classic. Thenceforth, he continued to make of import contributions to every department of comparative beefcake and zoology for a menstruation of over 50 years. In the sponges, Owen was the first to describe the at present well-known Venus' Bloom Basket or Euplectella (1841, 1857). Amongst Entozoa, his nearly noteworthy discovery was that of Trichina spiralis (1835), the parasite infesting the muscles of man in the disease at present termed trichinosis (come across besides, however, Sir James Paget). Of Brachiopoda he made very special studies, which much advanced knowledge and settled the nomenclature that has long been accepted. Amidst Mollusca, he described not merely the pearly nautilus merely also Spirula (1850) and other Cephalopoda, both living and extinct, and it was he who proposed the universally-accepted subdivision of this grade into the ii orders of Dibranchiata and Tetrabranchiata (1832). In 1852 Owen named Protichnites – the oldest footprints found on land.[13] Applying his knowledge of anatomy, he correctly postulated that these Cambrian trackways were made by an extinct type of arthropod,[13] and he did this more than 150 years before any fossils of the animal were establish.[14] [15] Owen envisioned a resemblance of the animal to the living arthropod Limulus,[13] which was the subject of a special memoir he wrote in 1873.

Fish, reptiles, birds, and naming of dinosaurs

Richard Owen in 1856 with the skull of a crocodile

Owen's coining of the word dinosaur in 1841

Owen'due south technical descriptions of the Vertebrata were nonetheless more than numerous and extensive than those of the invertebrate animals. His Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of Vertebrates (3 vols. London 1866–1868) was indeed the effect of more personal research than any like work since Georges Cuvier'southward Leçons d'anatomie comparée. He non but studied existing forms but also devoted great attention to the remains of extinct groups, and followed Cuvier, the pioneer of vertebrate paleontology. Early in his career, he made exhaustive studies of teeth of existing and extinct animals and published his profusely illustrated work on Odontography (1840–1845). He discovered and described the remarkably complex structure of the teeth of the extinct animals which he named Labyrinthodontia. Amongst his writings on fish, his memoir on the African lungfish, which he named Protopterus, laid the foundations for the recognition of the Dipnoi by Johannes Müller. He also later pointed out the serial connection between the teleostean and ganoid fishes, grouping them in i sub-class, the Teleostomi.

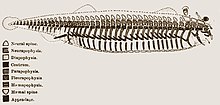

Nigh of his work on reptiles related to the skeletons of extinct forms and his primary memoirs, on British specimens, were reprinted in a connected series in his History of British Fossil Reptiles (4 vols. London 1849–1884). He published the offset important full general account of the bully grouping of Mesozoic land-reptiles, and he coined the name Dinosauria from Greek δεινός (deinos) "terrible, powerful, wondrous" + σαύρος (sauros) "lizard".[2] [iii] Owen used 3 genera to define the dinosaurs: the carnivorous Megalosaurus, the herbivorous Iguanodon and armoured Hylaeosaurus', specimens uncovered in southern England.[3] He also showtime recognized the curious early on Mesozoic synapsids, with affinities both to amphibians and mammals, which he termed Anomodontia (the mammal-like synapsids, Therapsida). Most of these were obtained from South Africa, offset in 1845 (Dicynodon) and eventually furnished materials for his Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of Southward Africa, issued by the British Museum, in 1876. Among his writings on birds, his classical memoir on the kiwi (1840–1846), a long series of papers on the extinct Dinornithidae of New Zealand, other memoirs on Aptornis, the takahe, the dullard and the great auk, may be especially mentioned. His monograph on Archaeopteryx (1863), the long-tailed, toothed bird from the Bavarian lithographic stone, is also an epoch-making work.

With Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Owen helped create the first life-size sculptures depicting dinosaurs every bit he idea they might have appeared. Some models were initially created for the Great Exhibition of 1851, simply 33 were eventually produced when the Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham, in South London. Owen famously hosted a dinner for 21 prominent men of science inside the hollow physical Iguanodon on New year's day's Eve 1853. However, in 1849, a few years before his expiry in 1852, Gideon Mantell had realised that Iguanodon, of which he was the discoverer, was non a heavy, pachyderm-like animal,[sixteen] as Owen was proposing, but had slender forelimbs; his death left him unable to participate in the creation of the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures, and and so Owen'due south vision of dinosaurs became that seen by the public. He had nearly two dozen lifesize sculptures of various prehistoric animals congenital out of physical sculpted over a steel and brick framework; two Iguanodon, 1 standing and i resting on its belly, were included.

Work on mammals

Owen was granted right of first refusal on whatsoever freshly dead creature at the London Zoo. His wife one time arrived habitation to find the carcass of a newly deceased rhino in her front hallway.[8]

With regard to living mammals, the more striking of Owen's contributions chronicle to the monotremes, marsupials and the anthropoid apes. He was also the showtime to recognize and name the two natural groups of typical Ungulate, the odd-toed (Perissodactyla) and the even-toed (Artiodactyla), while describing some fossil remains, in 1848. Most of his writings on mammals, nonetheless, deal with extinct forms, to which his attention seems to take been first directed past the remarkable fossils collected by Charles Darwin, in South America. Toxodon, from the pampas, was then described and gave the earliest clear testify of an extinct generalized hoof beast, a pachyderm with affinities to the Rodentia, Edentata and herbivorous Cetacea. Owen's involvement in S American extinct mammals so led to the recognition of the giant armadillo, which he named Glyptodon (1839) and to classic memoirs on the behemothic basis-sloths, Mylodon (1842) and Megatherium (1860), too other of import contributions. Owen also showtime described the false killer whale in 1863.

At the same time, Sir Thomas Mitchell'south discovery of fossil bones, in New South Wales, provided textile for the first of Owen'southward long series of papers on the extinct mammals of Australia, which were eventually reprinted in volume-form in 1877. He described Diprotodon (1838) and Thylacoleo (1859), and extinct species kangaroos and wombats of gigantic size. Near fossil fabric found in Commonwealth of australia and New Zealand was initially sent to England for expert examination, and with the help of the local collectors Owen became the commencement authority on the palaeontology of the region.[17] While occupied with so much material from abroad, Owen was too busily collecting facts for an exhaustive piece of work on similar fossils from the British Isles and, in 1844–1846, he published his History of British Fossil Mammals and Birds, which was followed by many later memoirs, notably his Monograph of the Fossil Mammalia of the Mesozoic Formations (Palaeont. Soc., 1871). One of his latest publications was a footling piece of work entitled Antiquity of Man as deduced from the Discovery of a Human being Skeleton during Excavations of the Docks at Tilbury (London, 1884).

Owen, Darwin, and the theory of evolution

Post-obit the voyage of the Beagle, Darwin had at his disposal a considerable collection of specimens and, on 29 October 1836, he was introduced by Charles Lyell to Owen, who agreed to work on fossil bones collected in South America. Owen's subsequent revelations, that the extinct giant creatures were rodents and sloths, showed that they were related to current species in the same locality, rather than being relatives of similarly sized creatures in Africa, as Darwin had originally idea. This was one of the many influences that led Darwin later to codify his own ideas on the concept of natural selection.

At this time, Owen talked of his theories, influenced by Johannes Peter Müller, that living matter had an "organising energy", a life-force that directed the growth of tissues and besides determined the lifespan of the individual and of the species. Darwin was reticent well-nigh his own thoughts, understandably, when, on xix Dec 1838, as secretary of the Geological Society of London, he saw Owen and his allies ridicule the Lamarckian 'heresy' of Darwin's onetime tutor, Robert Edmund Grant. In 1841, when the recently married Darwin was ill, Owen was i of the few scientific friends to visit; however, Owen's opposition to any hint of transmutation made Darwin keep quiet most his hypothesis.

Sometime during the 1840s Owen came to the decision that species arise as the event of some sort of evolutionary process.[vii] He believed that there was a total of six possible mechanisms: parthenogenesis, prolonged development, premature birth, congenital malformations, Lamarckian cloudburst, Lamarckian hypertrophy and transmutation,[7] of which he thought transmutation was the to the lowest degree likely.[7] The historian of scientific discipline Evelleen Richards has argued that Owen was likely sympathetic to developmental theories of evolution, only backed abroad from publicly proclaiming them later the disquisitional reaction that had greeted the anonymously published evolutionary volume Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in 1844 (it was revealed only decades later that the book had been authored by publisher Robert Chambers). Owen had been criticized for his own evolutionary remarks in his Nature of the Limbs in 1849.[18] At the finish of On the Nature of Limbs Owen had suggested that humans ultimately evolved from fish as the result of natural laws,[19] which resulted in his existence criticized in the Manchester Spectator for denying that species such equally humans were created past God.[vii]

During the development of Darwin's theory, his investigation of barnacles showed, in 1849, how their sectionalisation related to other crustaceans, showing how they had diverged from their relatives. To both Darwin and Owen such "homologies" in comparative anatomy were evidence of descent. Owen demonstrated fossil evidence of an evolutionary sequence of horses, as supporting his idea of evolution from archetypes in "ordained continuous condign" and, in 1854, gave a British Association talk on the impossibility of unmerciful apes, such every bit the recently discovered gorilla, standing erect and beingness transmuted into men, but Owen did not rule out the possibility that humans had evolved from other extinct animals by evolutionary mechanisms other than transmutation. Working-class militants were trumpeting man'south monkey origins.[ citation needed ] To shell these ideas, Owen, as President-elect of the Royal Clan,[ description needed ] announced his authoritative anatomical studies of primate brains, claiming that the human brain had structures that apes brains did not, and that therefore humans were a dissever sub-class, starting a dispute which was afterward satirised as the Great Hippocampus Question. Owen's primary argument was that humans have much larger brains for their torso size than other mammals including the keen apes.[4] Darwin wrote that "I cannot eat Man [being that] singled-out from a Chimpanzee". The combative Thomas Henry Huxley used his March 1858 Royal Institution lecture to deny Owen's claim and affirmed that structurally, gorillas are as close to humans as they are to baboons. He believed that the "mental & moral faculties are essentially... the same kind in animals & ourselves". This was a articulate deprival of Owen'southward claim for human uniqueness, given at the same venue.

This 1847 diagram by Richard Owen shows his conceptual archetype for all vertebrates

On the publication of Darwin's theory, in On The Origin of Species, he sent a complimentary copy to Owen, saying "it will seem 'an abomination'". Owen was the first to respond, courteously claiming that he had long believed that "existing influences" were responsible for the "ordained" nascence of species. Darwin at present had long talks with him and Owen said that the volume offered the best caption "e'er published of the mode of germination of species", although he still had the gravest doubts that transmutation would bestialize human being. It appears that Darwin had bodacious Owen that he was looking at everything as resulting from designed laws, which Owen interpreted as showing a shared belief in "Creative Power".

As head of the Natural History Collections at the British Museum, Owen received numerous inquiries and complaints near the Origin. His own views remained unknown: when emphasising to a Parliamentary committee the demand for a new Natural History museum, he pointed out that "The whole intellectual world this yr has been excited by a book on the origin of species; and what is the consequence? Visitors come to the British Museum, and they say, 'Let us see all these varieties of pigeons: where is the tumbler, where is the pouter?' and I am obliged with shame to say, I tin show you none of them" .... "As to showing yous the varieties of those species, or of any of those phenomena that would aid one in getting at that mystery of mysteries, the origin of species, our space does not permit; but surely there ought to be a space somewhere, and, if non in the British Museum, where is it to exist obtained?"

However, Huxley'due south attacks were making their marker. In April 1860 the Edinburgh Review included Owen's anonymous review of the Origin. In it Owen showed his anger at what he saw as Darwin'southward caricature of the creationist position, and his ignoring Owen's "axiom of the continuous operation of the ordained condign of living things". Besides as attacking Darwin'southward "disciples", Hooker and Huxley, for their "short-sighted adherence", he thought that the book symbolised the sort of "abuse of science... to which a neighbouring nation, some lxx years since, owed its temporary degradation" in a reference to the French Revolution. Darwin thought it "Spiteful, extremely malignant, clever, and... dissentious" and later commented that "The Londoners say he is mad with envy because my book is so talked nigh. It is painful to be hated in the intense degree with which Owen hates me."

During the reaction to Darwin's theory, Huxley's arguments with Owen continued. Owen tried to smear Huxley, by portraying him as an "abet of man's origins from a transmuted ape" and i of his contributions to the Athenaeum was titled "Ape-Origin of Man as Tested past the Encephalon". In 1862 (and on other occasions) Huxley took the opportunity to suit demonstrations of ape brain anatomy (e.g. at the BA meeting, where William Bloom performed the autopsy). Visual evidence of the supposedly missing structures (posterior cornu and hippocampus minor) was used, in outcome, to indict Owen for perjury. Owen had argued that the absenteeism of those structures in apes were continued with the lesser size to which the ape brains grew, simply he and so conceded that a poorly developed version might be construed as nowadays without preventing him from arguing that encephalon size was still the major way of distinguishing apes and humans.[4] Huxley'south campaign ran over 2 years and was devastatingly successful at persuading the overall scientific community, with each "slaying" beingness followed past a recruiting drive for the Darwinian cause. The spite lingered. While Owen had argued that humans were distinct from apes by virtue of having large brains, Huxley claimed that racial variety blurred whatsoever such distinction. In his paper criticizing Owen, Huxley direct states: "if nosotros place A, the European brain, B, the Bosjesman brain, and C, the orang brain, in a serial, the differences between A and B, so far as they take been ascertained, are of the same nature as the primary of those between B and C".[20] Owen countered Huxley by saying the brains of all human races were really of similar size and intellectual ability, and that the fact that humans had brains that were twice the size of big apes like male person gorillas, even though humans had much smaller bodies, fabricated humans distinguishable.[4] When Huxley joined the Zoological Order Council, in 1861, Owen left and, in the following twelvemonth, Huxley moved to stop Owen from being elected to the Majestic Society Council, accusing him "of wilful & deliberate falsehood". (See also Thomas Henry Huxley.)

In January 1863, Owen bought the Archaeopteryx fossil for the British Museum. It fulfilled Darwin's prediction that a proto-bird with unfused wing fingers would be plant, although Owen described it unequivocally as a bird.

The feuding between Owen and Darwin'due south supporters continued. In 1871, Owen was institute to exist involved in a threat to terminate government funding of Joseph Dalton Hooker's botanical collection, at Kew, mayhap trying to bring it under his British Museum. Darwin commented that "I used to exist aback of hating him so much, merely at present I will carefully cherish my hatred & antipathy to the last days of my life".

Legacy

Owen'due south detailed memoirs and descriptions require laborious attention in reading, on account of their complex terminology and ambiguous modes of expression. The fact that very piffling of his terminology has establish universal favour causes them to be more generally neglected than they otherwise would be. At the aforementioned time, information technology must exist remembered that he was a pioneer in concise anatomical nomenclature and, then far at least every bit the vertebrate skeleton is concerned, his terms were based on a advisedly reasoned philosophical scheme, which first clearly distinguished between the now-familiar phenomena of illustration and homology. Owen'southward theory of the Archetype and Homologies of the Vertebrate Skeleton (1848), subsequently illustrated too by his little piece of work On the Nature of Limbs (1849), regarded the vertebrate frame as consisting of a serial of fundamentally identical segments, each modified co-ordinate to its position and functions. Much of it was fanciful and failed when tested by the facts of embryology, which Owen systematically ignored, throughout his piece of work. However, though an imperfect and distorted view of certain great truths, information technology possessed a distinct value at the time of its conception.

Caricature of an elderly Owen, captioned "Old Bones", in the London magazine Vanity Fair, March 1873

To the discussion of the deeper problems of biological philosophy, he made scarcely any direct and definite contributions. His generalities rarely extended beyond strict comparative beefcake, the phenomena of adaptation to role and the facts of geographical or geological distribution. His lecture on virgin reproduction or parthenogenesis, however, published in 1849, contained the essence of the germ plasm theory, elaborated after past August Weismann and he made several vague statements concerning the geological succession of genera and species of animals and their possible derivation one from another. He referred, particularly, to the changes exhibited by the successive forerunners of the crocodiles (1884) and horses (1868) but it has never become articulate how much of the modernistic doctrines of organic development he admitted. He contented himself with the bare remark that "the inductive demonstration of the nature and style of performance of the laws governing life would henceforth be the bully aim of the philosophical naturalist."

He was the first managing director in Natural History Museum in London and his statue was in the chief hall there until 2009, when information technology was replaced with a statue of Darwin. A bosom of Owen past Alfred Gilbert (1896) is held in the Hunterian Museum, London. There is a blueish plaque in his honour at Lancaster Royal Grammar School. A species of Fundamental American lizard, Diploglossus owenii, was named in his honour past French herpetologists André Marie Constant Duméril and Gabriel Bibron in 1839.[21] The Sir Richard Owen pub in central Lancaster is named in his honour.[22]

Conflicts with his peers

Owen has been described by some every bit a malicious, quack and hateful individual. He has been described in one biography as being a "social experimenter with a penchant for sadism. Addicted to controversy and driven by airs and jealousy". Deborah Cadbury stated that Owen possessed an "almost fanatical egoism with a callous delight in savaging his critics." An Oxford Academy professor once described Owen as "a damned liar. He lied for God and for malice".[23] Gideon Mantell claimed information technology was "a pity a man and so talented should be and so dastardly and envious". Richard Broke Freeman described him every bit "the nearly distinguished vertebrate zoologist and palaeontologist ... but a most deceitful and odious homo".[24] Charles Darwin stated that "No i fact tells and so strongly confronting Owen ... every bit that he has never reared one pupil or follower."[25]

Owen famously credited himself and Georges Cuvier with the discovery of the Iguanodon, completely excluding any credit for the original discoverer of the dinosaur, Gideon Mantell. This was not the starting time or concluding time Owen would falsely claim a discovery every bit his own. It has as well been suggested by some authors, including Bill Bryson in A Short History of Nearly Everything, that Owen even used his influence in the Royal Guild to ensure that many of Mantell's research papers were never published. Owen was finally dismissed from the Royal Club's Zoological Council for plagiarism.[26]

1873 extravaganza of Owen "riding his hobby", past Frederick Waddy

When Mantell suffered an accident that left him permanently bedridden, Owen exploited the opportunity by renaming several dinosaurs which had already been named past Mantell, even having the audacity to claim credit for their discovery himself. When Mantell finally died in 1852, an obituary carrying no byline derided Mantell every bit petty more than a mediocre scientist, who brought forth few notable contributions. The obituary's authorship was universally attributed to Owen by every geologist. The president of the Geological Lodge claimed that it "bespeaks of the lamentable coldness of the heart of the writer". Owen was subsequently denied the presidency of the club for his repeated and pointed animosity towards Gideon Mantell.

Even more boggling was the way Owen ignored the genuine scientific content of Mantell'southward work. For example, despite the paucity of finds Mantell had worked out that some dinosaurs were bipedal, including Iguanodon. This remarkable insight was totally ignored by Owen, whose instructions for the Crystal Palace models by Waterhouse Hawkins portrayed Iguanodon as grossly overweight and quadrupedal. Mantell did not live to witness the discovery in 1878 of articulated skeletons in a Belgium coal-mine that showed Iguanodon was mostly bipedal (and in that stance could use its thumb for defence). Owen made no comment or retraction; he never did on whatsoever errors he made. Moreover, since the earliest known dinosaurs were bipedal, Mantell's idea was indeed insightful.

Owen with his granddaughter Emily

Despite originally starting out on practiced terms with Darwin, Owen was highly critical of the Origin in large part because Darwin did not refer much to the previous scientific theories of evolution that had been proposed by people like Chambers and himself, and instead compared the theory of evolution by natural selection with the unscientific theory in the Bible.

Another reason for his criticism of the Origin, some historians claim, was that Owen felt upstaged past Darwin and supporters such equally Huxley, and his judgment was clouded by jealousy. Owen in Darwin's opinion was "Spiteful, extremely malignant, clever; the Londoners say he is mad with envy because my book is and then talked almost".[27] "It is painful to be hated in the intense caste with which Owen hates me".[28] Owen as well resorted to the same subterfuge he used against Mantell, writing another anonymous article in the Edinburgh Review in April 1860. In the article, Owen was critical of Darwin for not offer many new observations, and heaped praise (in the third person) upon himself, while being conscientious not to associate any particular comment with his ain proper name.[29] Owen did praise, yet, the Origin'due south description of Darwin'due south work on insect behavior and dove breeding as Huxley, Thomas H., (1861), "On the Zoological Relations of Man with the Lower Animals", Natural History Review ane: 67–84."real gems".[30]

Owen was also a political party to the threat to end government funding of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew botanical collection (encounter Attacks on Hooker and Kew), orchestrated past Acton Smee Ayrton:

- "In that location is no dubiety that rivalry resulted betwixt the British Museum, where at that place was the very important Herbarium of the Section of Botany, and Kew. The rivalry at times became extremely personal, particularly between Joseph Hooker and Owen... At the root was Owen'south feeling that Kew should be subordinate to the British Museum (and to Owen) and should not be allowed to develop as an contained scientific institution with the reward of a dandy botanic garden."[31]

It has been suggested by some authors that the portrayal of Owen every bit a vindictive and treacherous man was fostered and encouraged by his rivals (particularly Darwin, Hooker and Huxley) and may be somewhat undeserved. In the first part of his career he was regarded rightly as one of the great scientific figures of the age. In the 2d part of his career his reputation slipped. This was not due solely to his underhanded dealings with colleagues; it was also due to serious errors of scientific judgement that were discovered and publicized. A fine example was his conclusion to allocate human being in a separate subclass of the Mammalia (see Man'south place in nature). In this Owen had no supporters at all. Too, his unwillingness to come off the fence apropos evolution became increasingly damaging to his reputation as time went on. Owen continued working after his official retirement at the age of 79, but he never recovered the good opinions he had garnered in his younger days.[32] [33]

Bibliography

- Memoir on the Pearly Nautilus (1832)

- Odontography (1840–1845)

- Clarification of the Skeleton of an Extinct Gigantic Sloth (1842)

- On the Classic and Homologies of the Vertebrate Skeleton (1848)

- History of British Fossil Reptiles (4 vols., 1849–1884)

- On the Nature of Limbs (1849)

- Palæontology or a Systematic Summary of Extinct Animals and Their Geological Relations (1860)

- Archaeopteryx (1863)

- Beefcake of Vertebrates (1866) Image from

- Available at Google Books:

- Book I, Fishes and Reptiles

- Volume Ii, Birds and Mammals

- Book Three, Mammals

- Memoir of the Dullard (1866) Full book on Wiki commons

- Monograph of the Fossil Mammalia of the Mesozoic Formations (1871)

- Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa (1876)

- Artifact of Human being as deduced from the Discovery of a Human Skeleton during Excavations of the Docks at Tilbury (1884)

References

- ^ a b Shindler, Karolyn (seven December 2010). "Richard Owen: the greatest scientist you've never heard of". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 19 Feb 2017.

- ^ a b Owen, Richard (1841). "Report on British fossil reptiles. Role II". Report of the Eleventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science; Held at Plymouth in July 1841. Report of the ... Meeting of the British Clan for the Advocacy of Scientific discipline (1833): lx–204. ; see p. 103. From p. 103: "The combination of such characters ... will, it is presumed, be deemed sufficient ground for establishing a distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria*. (*Gr. δεινός, fearfully great; σαύρος, a lizard. ... )"

- ^ a b c "Sir Richard Owen: The human being who invented the dinosaur". BBC. 18 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d Cosans, Christopher E. (2009). Owen'southward Ape & Darwin's Bulldog: Beyond Darwinism and Creationism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 1–192. ISBN978-0-253-22051-6.

- ^ Amundson, Ron (2007). The Irresolute Role of the Embryo in Evolutionary Idea: Roots of Evo-Devo. New York: Cambridge University of Press. pp. 1–296. ISBN978-0521806992.

- ^ Wilson, Tony (2016). "175th Ceremony Special Outcome: Introduction" (PDF). Periodical of Microscopy. doi:x.1111/(ISSN)1365-2818.

- ^ a b c d due east Rupke, Nicolaas A. (1994). Richard Owen: Victorian Naturalist. New Haven: Yale University Printing. pp. 1–484. ISBN978-0300058208.

- ^ a b Bryson, Bill (2003). A Short History of Nearly Everything. London: Doubleday. pp. 1–672. ISBN978-0-7679-0817-7.

- ^ "Eminent persons: Biographies reprinted from the Times, Vol V, 1891–1892 - Sir Richard Owen (Obituary)". Macmillan & Co. 1896: 291–299.

- ^ "Richard Owen (1804 - 1892)". Royal Netherlands University of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org . Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Regal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN0-902-198-84-Ten.

- ^ a b c Owen, Richard (1852). "Description of the impressions and footprints of the Protichnites from the Potsdam sandstone of Canada". Geological Society of London Quarterly Journal. viii (1–2): 214–225. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1852.008.01-02.26. S2CID 130712914.

- ^ Collette, Joseph H.; Hagadorn, James West. (2010). "3-Dimensionally Preserved Arthropods from Cambrian Lagerstätten of Quebec and Wisconsin". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (4): 646–667. doi:10.1666/09-075.i. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 130064618.

- ^ Collette, Joseph H; Gass, Kenneth C; Hagadorn, James W (2012). "Protichnites eremita unshelled? Experimental model-based neoichnology and new bear witness for a euthycarcinoid affinity for this ichnospecies". Journal of Paleontology. 83 (three): 442–454. doi:10.1666/xi-056.i. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 129234373.

- ^ Mantell, Gideon A. (1851). Petrifications and their teachings: or, a handbook to the gallery of organic remains of the British Museum. London: H. Chiliad. Bohn. OCLC 8415138.

- ^ Vickers-Rich, P. (1993). Wild animals of Gondwana. NSW: Reed. pp. 49–51. ISBN0730103153.

- ^ Richards, Evellen (1987). "A Question of Belongings Rights: Richard Owen'southward Evolutionism Reassessed". British Journal for the History of Scientific discipline. twenty (2): 129–171. doi:10.1017/S0007087400023724. JSTOR 4026305. S2CID 170268846.

- ^ Owen, 2007, p. 86

- ^ Huxley, Thomas Henry (1861). "On the Zoological Relations of Man with the Lower Animals". Natural History Review. ane: 67–84.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. thirteen + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Owen, R.", p. 198).

- ^ "The Sir Richard Owen Lancaster". www.jdwetherspoon.com. J D Wetherspoon. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Rocky Route: Sir Richard Owen. Strangescience.net (28 May 2011). Retrieved on 17 September 2011.

- ^ Freeman, Richard Broke (2007). Charles Darwin: A companion. Darwin Online.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (2020). More Letters of Charles Darwin. Library of Alexandria. p. 153. ISBN9781465549129.

- ^ Bryson, Neb (2016). A Short History of Nearly Everything. Black Swan. p. 123. ISBN9781784161859.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1 July 2001). Darwin, Francis; Seward, A. C. (Albert Charles) (eds.). More than Letters of Charles Darwin – Volume 1 A Record of His Work in a Series of Hitherto Unpublished Letters – via Projection Gutenberg.

- ^ "Projection Gutenberg".

- ^ Darwin on the Origin of Species. Darwin.gruts.com. Retrieved on 17 September 2011.

- ^ Owen (published anonymously), Richard (1860). "Darwin on the Origin of Species". Edinburgh Review. 111: 487–532.

- ^ Turrill W.B. 1963. Joseph Dalton Hooker. Nelson, London. p90.

- ^ Desmond A. 1982. Archetypes and ancestors: paleontology in Victorian London 1850–1875. Muller, London.

- ^ Sir Richard Owen: the archetypal villain. Darwin.gruts.com. Retrieved on 17 September 2011.

Further reading

- Anonymous (1873). Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the twenty-four hours. Illustrated past Frederick Waddy. London: Tinsley Brothers. pp. 36–37. Retrieved 6 Jan 2011.

- Anonymous (1896). "SIR RICHARD OWEN (1804-1892) (Obituary Detect, Monday, December nineteen, 1892)". Eminent Persons: Biographies reprinted from The Times. Vol. V (1891-1892). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. pp. 291–299. Retrieved 7 March 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Amundson, Ron, (2007), The Changing Role of the Embryo in Evolutionary Thought: Roots of Evo-Devo. New York: Cambridge University of Printing.

- Bryson, Bill (2003). A Curt History of Nearly Everything. London: Doubleday. ISBN978-0-7679-0817-7.

- Cadbury, Deborah (2000). Terrible Lizard: The First Dinosaur Hunters and the Birth of a New Scientific discipline . New York: Henry Holt. ISBN978-0-8050-7087-three.

- Collette, Joseph H., Gass, Kenneth C. & Hagadorn, James Westward. (2012). "Protichnites eremita unshelled? Experimental model-based neoichnology and new testify for a euthycarcinoid analogousness for this ichnospecies". Journal of Paleontology. 86 (three): 442–454. doi:10.1666/11-056.1. S2CID 129234373.

{{cite periodical}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Collette, Joseph H. & Hagadorn, James Due west. (2010). "Three-dimensionally preserved arthropods from Cambrian Lagerstatten of Quebec and Wisconsin". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (4): 646–667. doi:10.1666/09-075.ane. S2CID 130064618.

- Cosans, Christopher, (2009), Owen's Ape & Darwin's Bulldog: Beyond Darwinism and Creationism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Desmond, Adrian & Moore, James (1991). Darwin. London: Michael Joseph, the Penguin Group. ISBN 0-7181-3430-3.

- Darwin, Francis, editor (1887). The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin: Including an Autobiographical Chapter (7th Edition). London: John Murray.

- Darwin, Francis & Seward, A. C., editors (1903). More letters of Charles Darwin: A tape of his work in a series of hitherto unpublished letters. London: John Murray.

- Huxley, Thomas H., (1861), "On the Zoological Relations of Man with the Lower Animals", Natural History Review ane: 67–84.

- Owen, Richard (1852). "Description of the impressions and footprints of the Protichnites from the Potsdam sandstone of Canada". Geological Society of London Quarterly Journal. viii (1–2): 214–225. doi:x.1144/GSL.JGS.1852.008.01-02.26. S2CID 130712914.

- Owen, Richard (published anonymously) (April 1860). "Darwin on the Origin of Species". Edinburgh Review. 111: 487–532. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- Owen, Richard (Jan 2007) [1849]. Amundson, Ron (ed.). On the Nature of Limbs: A Soapbox, with a preface by Brian Hall, and essays past Ron Amundson, Kevin Padian, Mary Winsor, and Jennifer Coggon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-64194-2. LCCN 2007009519. [1]

- Owen, Richard (Owen's grandson) (1894). The Life of Richard Owen. Vol. i. London: J. Murray. ISBN978-0-8478-1188-5. LCCN 03026819.

- Owen, Richard (Owen's grandson) (1894). The Life of Richard Owen. Vol. 2. London: J. Murray. ISBN978-0-8478-1188-five. LCCN 03026819.

- Richards, Evellen, (1987), "A Question of Property Rights: Richard Owen'southward Evolutionism Reassessed", British Periodical for the History of Science, 20: 129–171.

- Rupke, Nicolaas, (1994), Richard Owen: Victorian Naturalist. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Shindler, Karolyn. Richard Owen: the greatest scientist you've never heard of, The Telegraph, xvi Dec 2010. (accessed sixteen December 2010)

External links

-

Media related to Richard Owen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Richard Owen at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ Cosans, 2009, pp. 108–111

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Owen

0 Response to "Richard Owen Review of Origin and Other Works Summary"

Post a Comment